Webscraping Baseball Data using Python

Why Scrape Baseball Data?

In my desire to improve my fantasy team, I realized I was lacking data on quality starts, and thought it would be good to predict this. Before I could start modeling, I needed historical season data and projections, to form the basis for my training, validation, and test data. I planned to get this all from Baseball Reference and Fangraphs, neither of which has an API that makes it easy to get their data.

I wrote this post to describe my methods for webscraping projection data from Fangraphs, and season data from Baseball Reference. Along the way, I’ll introduce the Python tools I used, and offer a few insights about scraping in general. If you want to use my code to implement your own webscraper, you will find that, along with a more detailed write-up at my github repo.

A word of caution about webscraping: these methods work so long as the webpage remains the same (hence the word ‘ephemeral’ in the post description). Once the webpage is updated, some of the specific locations for the text of interest may also need to be updated, and the functions may need to be updated.

Scraping Fangraphs

Getting the Source Code

To scrape Fangraphs, I used the requests and BeautifulSoup libraries, along with re to use regular expressions to find and extract the data I need from the source code, and pandas to put it all into dataframes.

Fangraphs does not have dynamic content, which makes scraping their page possible with just the libraries above. For pages with dynamic content, like Baseball Reference, I needed to use Selenium, which I will cover later.

I have webscraped a few different sites, and some are friendlier to scrapers than others. While puzzling through my code to extract just the right part, or writing it iteratively in small pieces, I’ve submitted one too many requests to get the source, resulting in the site unceremoniously blocking me, preventing any further scraping activity. To avoid this, I usually start small, scraping one or two pages from the same site, and saving the source so I could work out my regular expressions separately, without submitting more requests.

For example, the function below takes a list of urls (I usually use 2-3 urls) as an argument, and appends the source from each url to a list.

def get_data(urls):

response = []

for i in urls:

response.append(requests.get(i))

return responseFrom this, I can parse the source with BeautifulSoup, which makes it easier to navigate through the source code to find the elements I want.

Finding the Right Elements

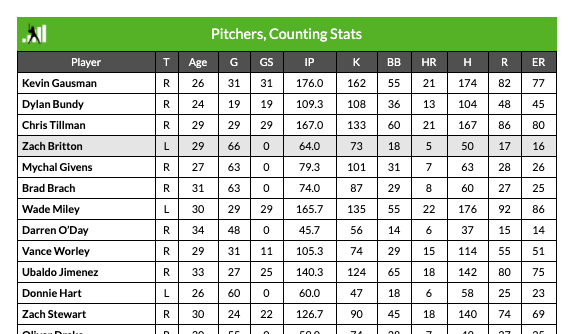

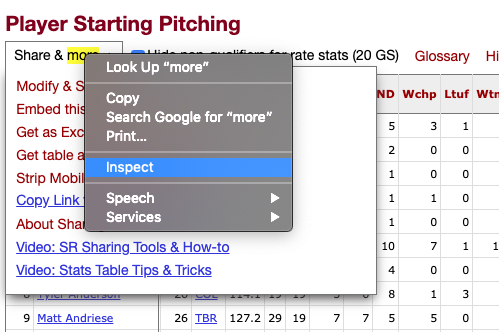

When webscraping, it helps to get comfortable with inspecting the source code, and understanding a bit of html. For instance, I want to get the contents of this table:

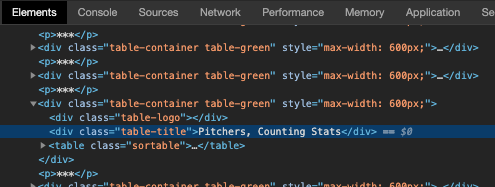

If I right click the table with my mouse and click “Inspect” in Google Chrome, a panel appears with this highlighted:

This lets me know the html tag, class, and text responsible for the table I’m interested in, and I can use Beautiful Soup to find that table in the source code to extract its values later. That would look something like the code below.

soup_object.find(text = 'Pitchers, Counting Stats').findNext()There are many functions available in Beautiful Soup to help navigate and find the right part of the page to extract, I highly recommend reading the documentation.

Regular expressions is also very helpful for extracting precisely what I want, when there isn’t a straightforward way to get it from BeautifulSoup. I’m not super confident with regex, so I usually like to test my expressions before I let them loose. This is a great way to make sure I’m retrieving what I want to retrieve.

The code below extracts the Team Name from the source code by keeping the first instance that matches the regex pattern.

team_clean = re.findall('[\s(A-z)]+[\|]', team_data)[0]Putting It All Together

Once I’ve extracted the data I want, I use pandas to put it all together into a dataframe. At this point, I can loop through my process for each of the pages I want to scrape from, and save the result as a csv, or as a pickle file. I am most familiar with saving my data as csv files, but I was introduced to pickling recently, and it’s changed my life. The best thing about pickle files is that they work well for pickling any kind of object, so you can pickle trained models, as well as dataframes. For this project, I stuck to saving dataframes as csvs.

Scraping Baseball Reference

Getting the Source Code

As I mentioned above, Baseball Reference has dynamic content, so parts of the page (including the table I want data from) only display once I scroll to them. This means that the page source code is different depending on how I interact with the page, and if I scrape the page before I scroll to the table, I’m not going to find the code for the table in the scraped source code.

The simple answer would be to manually scroll if I’m scraping one or two pages. But if I’m scraping multiple pages, and I want to automate scrolling, clicking, or other user behavior, I can use Selenium.

For pages with dynamic content, I’ve also found it useful to add a sleep timer from the time module, which pauses activity, allowing the website to fully load.

Using the code below, I can load the page for 2016 season data, and scroll far enough down the page to display the table.

driver.get('https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/2016-starter-pitching.shtml')

time.sleep(5)

driver.execute_script("window.scrollTo(0, 1500);")This action will display the table I want to scrape.

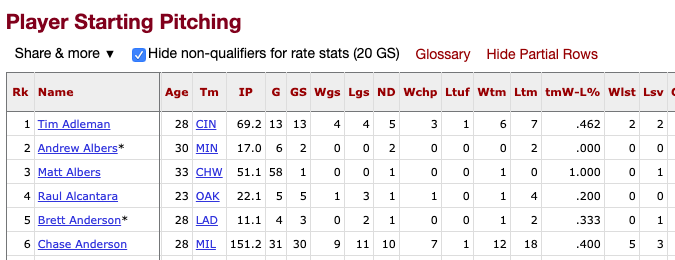

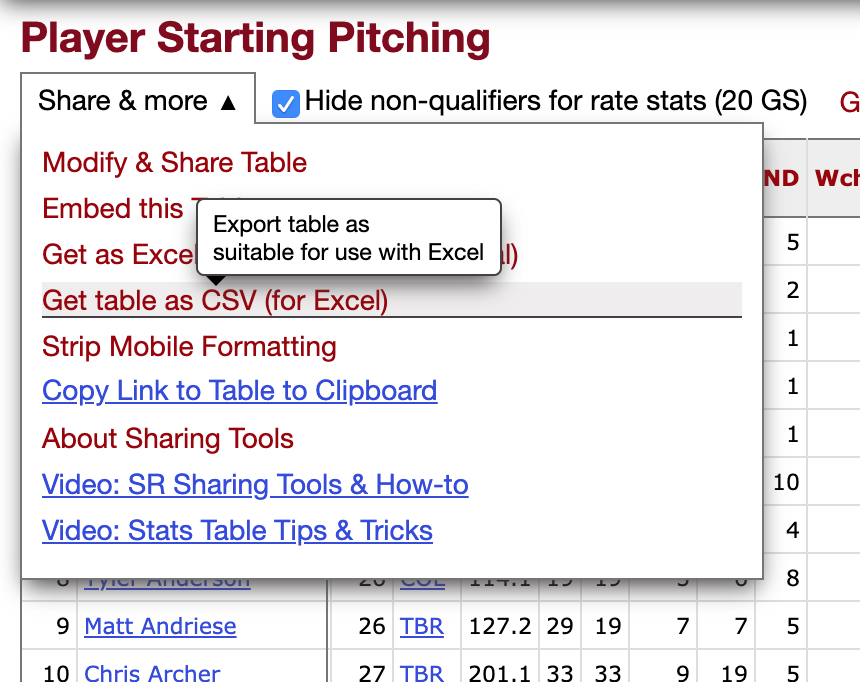

Baseball Reference offers an option to “Get table as CSV”, which will make it much easier for me to turn the scraped table into a pandas dataframe.

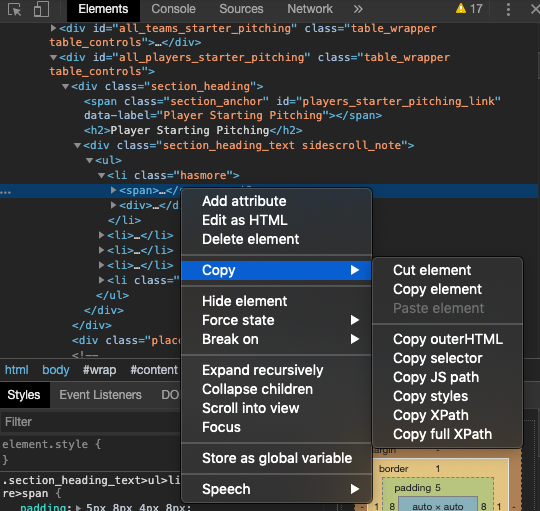

I can use Selenium to click on the menu options that make it possible, if I know where to click. Inspect is handy for this.

Selenium lets me use XPaths to locate specific parts of the source code (unlike Beautiful Soup), and I find this more straightforward. I can copy the XPath from the window that pops up when I inspect.

In the end, my code looks like this, which clicks on the menu, waits five seconds, and then clicks on the link that displays the table as a csv.

driver.find_element_by_xpath('//*[@id="all_players_starter_pitching"]/div[1]/div/ul/li[1]').click()

time.sleep(5)

driver.find_element_by_xpath('//*[@id="all_players_starter_pitching"]/div[1]/div/ul/li[1]/div/ul/li[4]/button').click()Now the page is displaying the content I want, and I can get the page source code and parse it using BeautifulSoup, as I did for the Fangraphs page.

Finding the Right Elements, and Putting It All Together

Now it’s a matter of navigating to the right part of source code and saving the part responsible for the table.

soup_object.find('pre', id = 'csv_players_starter_pitching')From here, I can process the data, and again use pandas to put it all together into a dataframe, and save it all as a csv. This is also where I would run a loop, iterating over each of the pages I want to scrape from.

Once I’m done using Selenium, I close the driver.

driver.close()Wrap Up

More comprehensive code for scraping can be found on my github repo. To see what I’m doing with all of this baseball data, see the next post.

This post was inspired by project work at Metis. Thanks for reading, and stay tuned for more posts on what I’m learning!